The new standard-work on the Runes, Rune magic and divination

A comprehensive guide to the runes, including detailed interpretations of the rune poems, reviews of primary sources, and analysis and illustrations of various runic artifacts. Ideal for both new and experienced runeologists.

What this book offers.

What sets this book apart from others about the runes?

Primary Sources

Each chapter on the runes includes detailed analyses of primary sources, archaeological data, and runic artifacts, enabling the reader to form their own opinions about each interpretation.

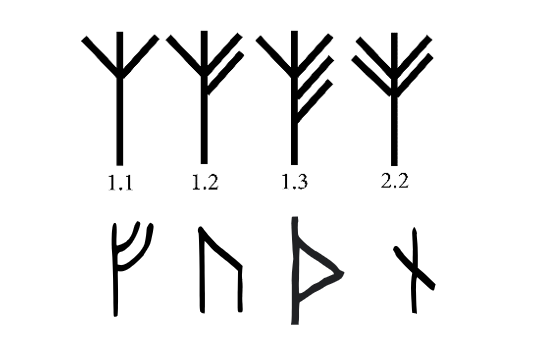

Detailed Illustrations

This book features numerous illustrations of runic artifacts that are not available elsewhere.

Cultural Context

Each subject is placed within its cultural context to make it accessible for a modern audience.

How the book is structured

Section 01

The Runes

The first section of the book contains a chapter for each of the Runes of the Futhark. Each Rune chapter includes an analysis of the Rune Poems, runic artifacts that have been found that use this rune for its magical meaning, an overview of relevant culture and sagas relating to the meaning of the Rune, and finally, each chapter ends with a way to experience the Runes in a modern context

Section 02

Magic

The second section of the book describes the different ways that Runes where used in magic. The chapter includes a overview of the cultural attitude towards to Galdr and seidr magic. An overview of Lodrunar, charm words, rune combinations and formulas used historically with artifacts as example. Finally there are examples on how to use these techniques to create your own charms.

Section 03

Divination

The third section of this chapter examines the history and modern uses of runes in divination. It also provides examples of rune spreads and practical guidance on how to use them.